-

2024 ~

-

2024

-

2023

-

2024

𓃗 materials↓

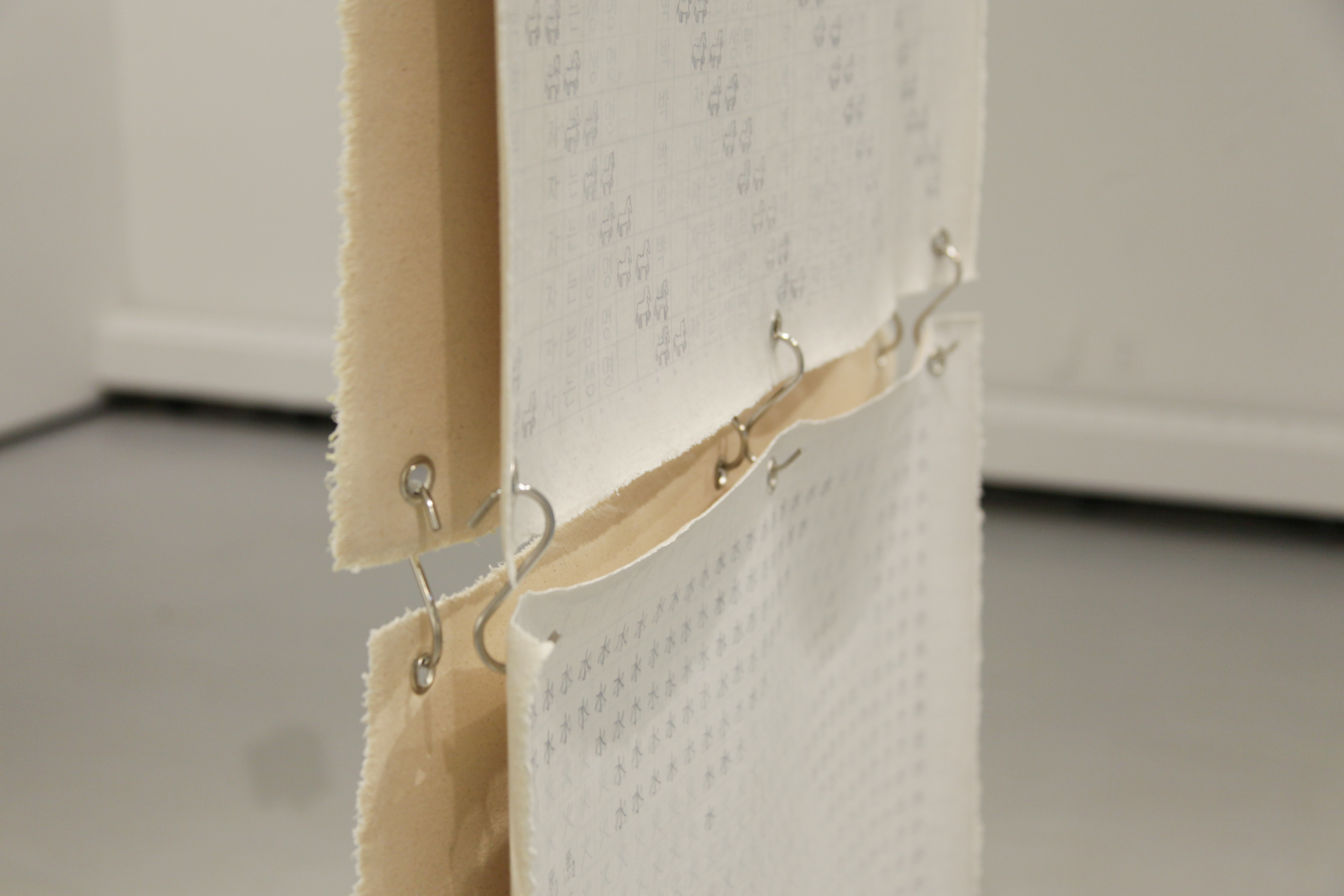

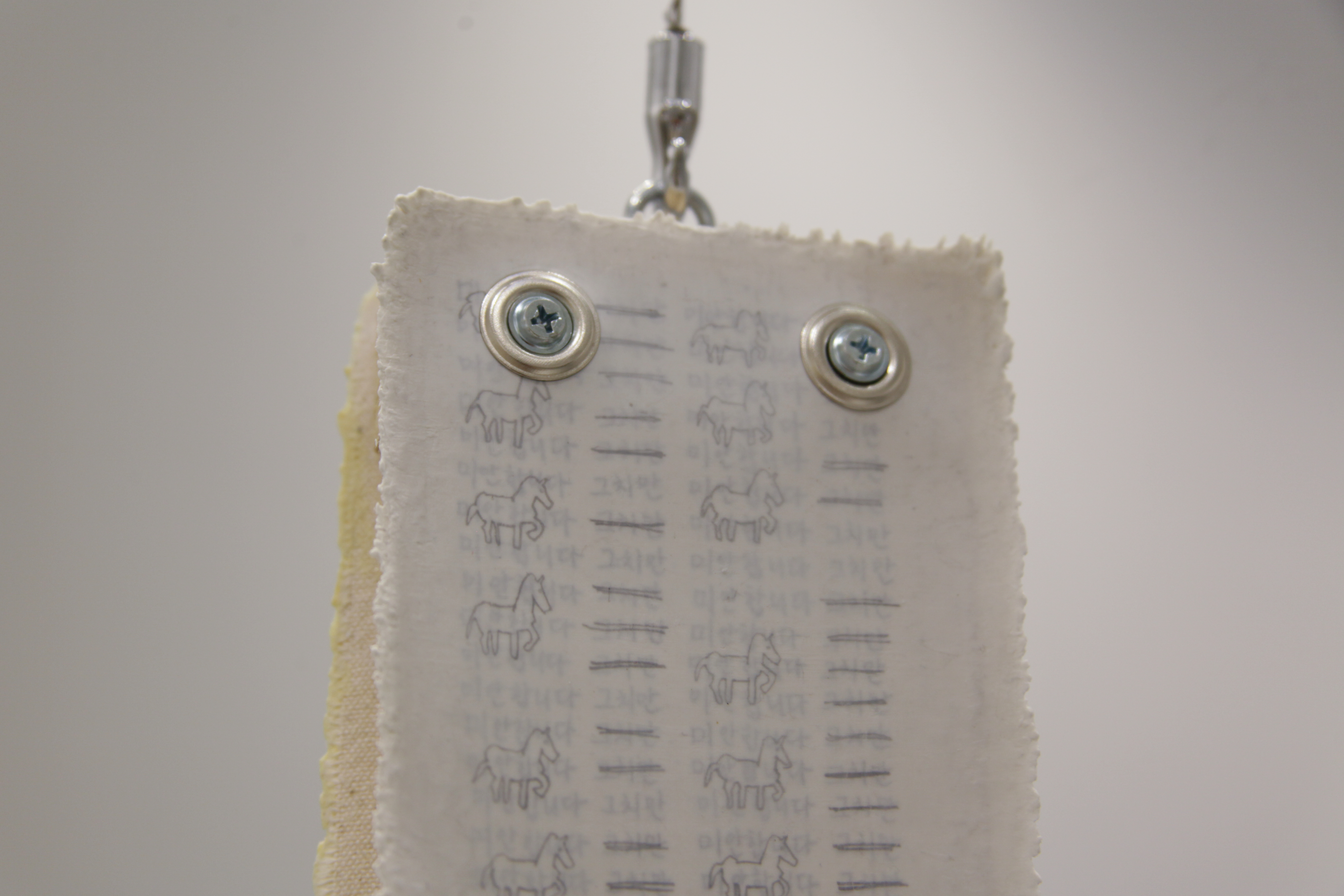

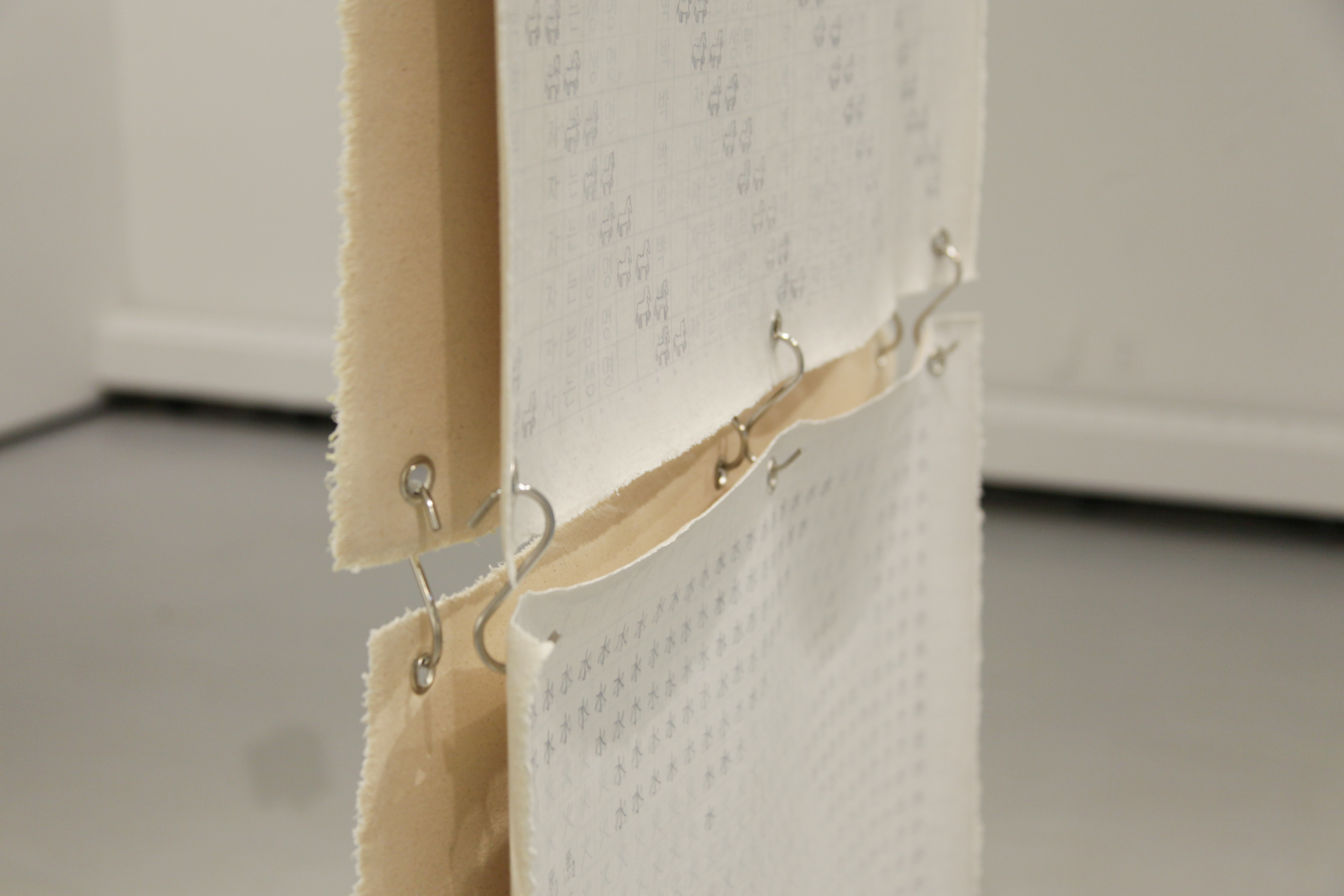

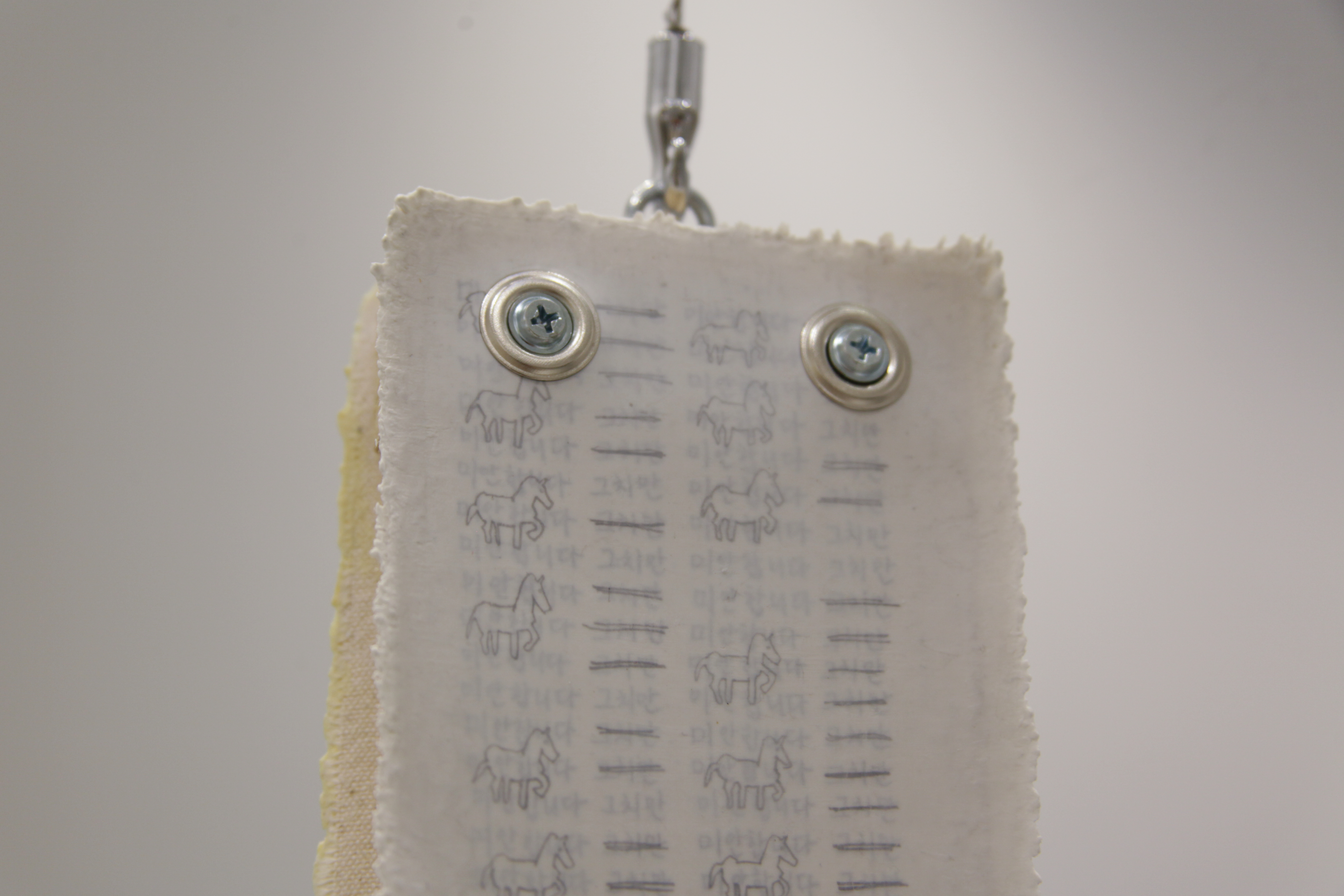

canvas, acrylic medium, graphite, acrylic paint, acrylic ink, waxed thread, oil paint, aluminum sheet metal, zinc screws, stainless steel grommets, stainless steel s-hooks

𓃗 dimensions↓

variable

𓃗 words↓

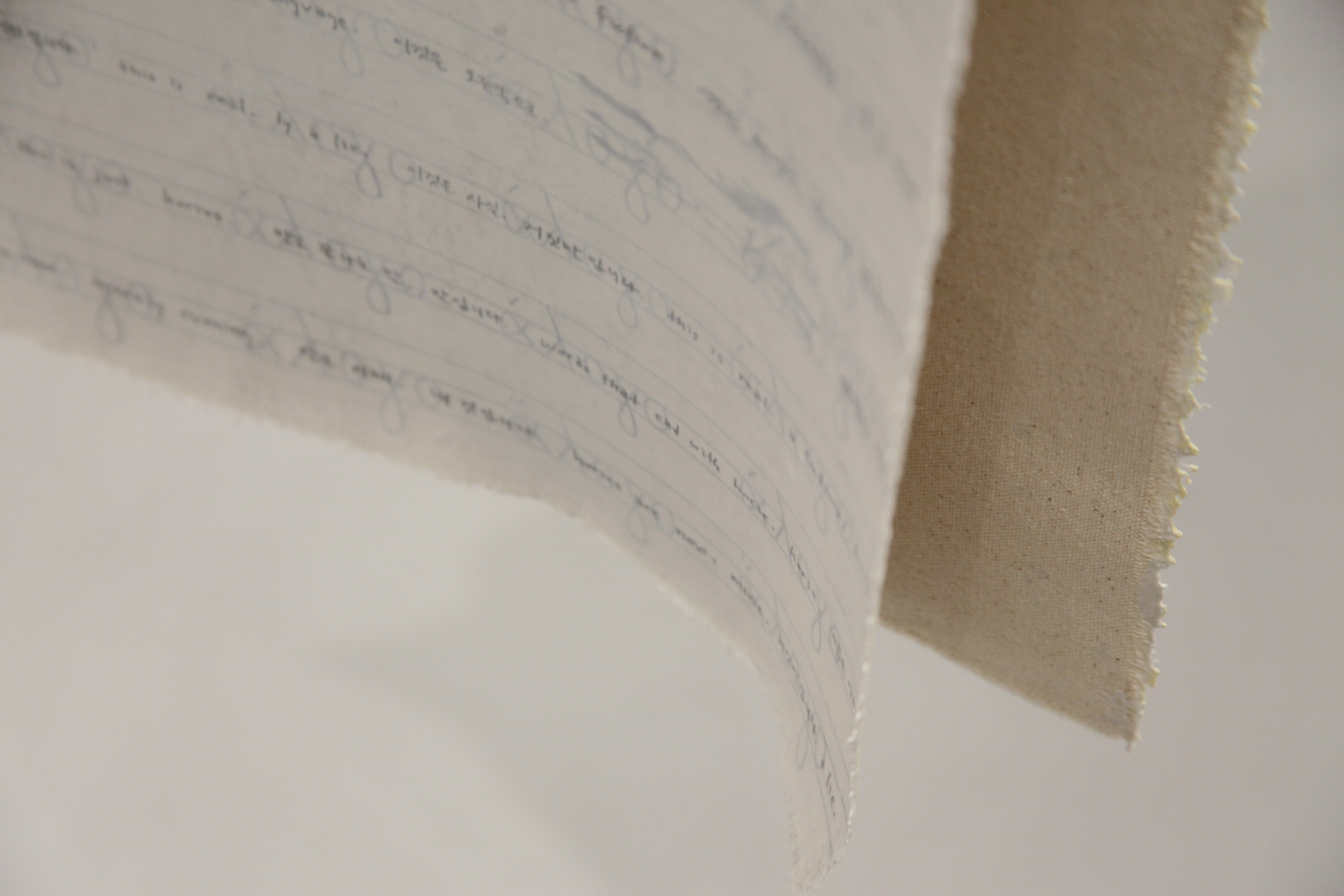

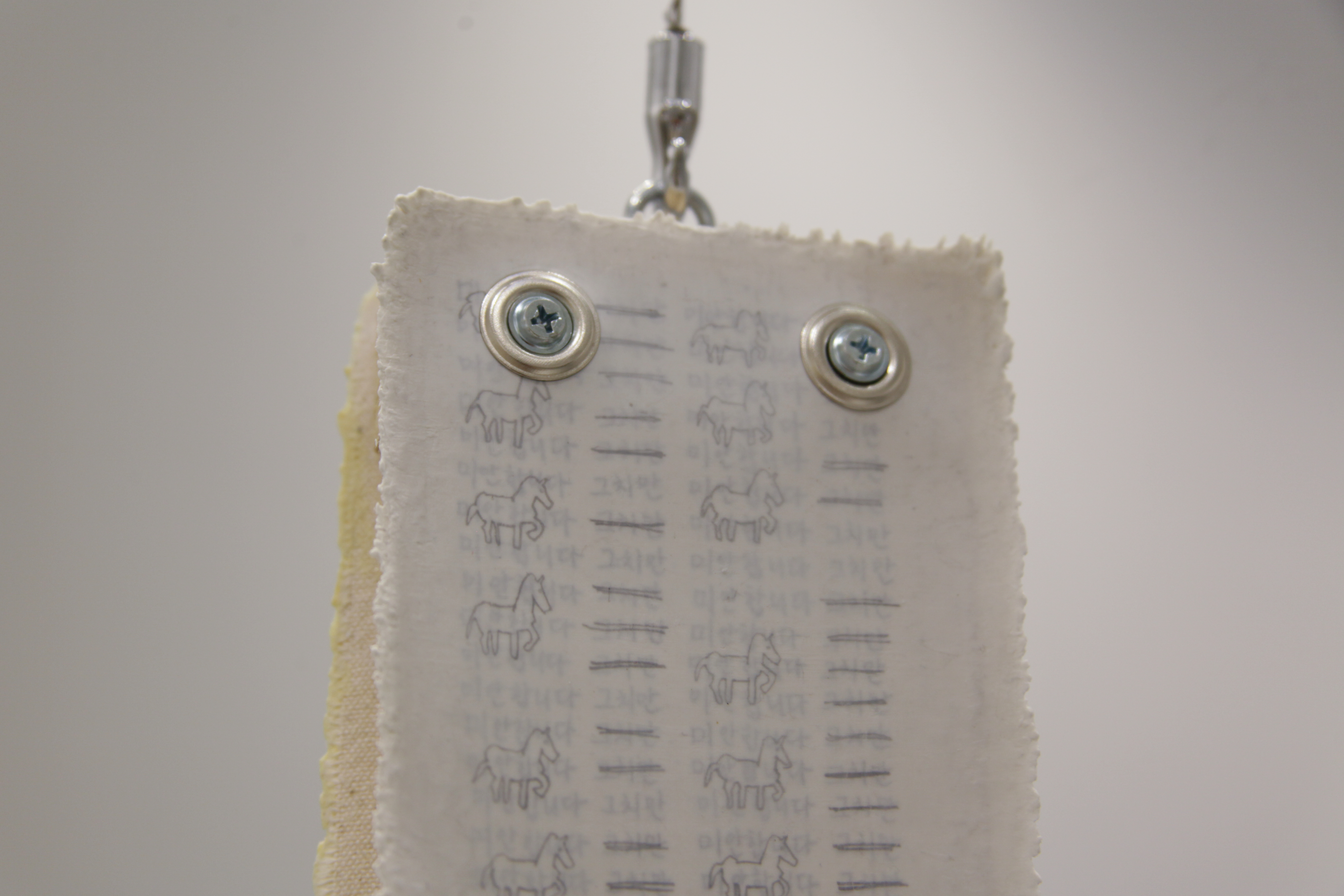

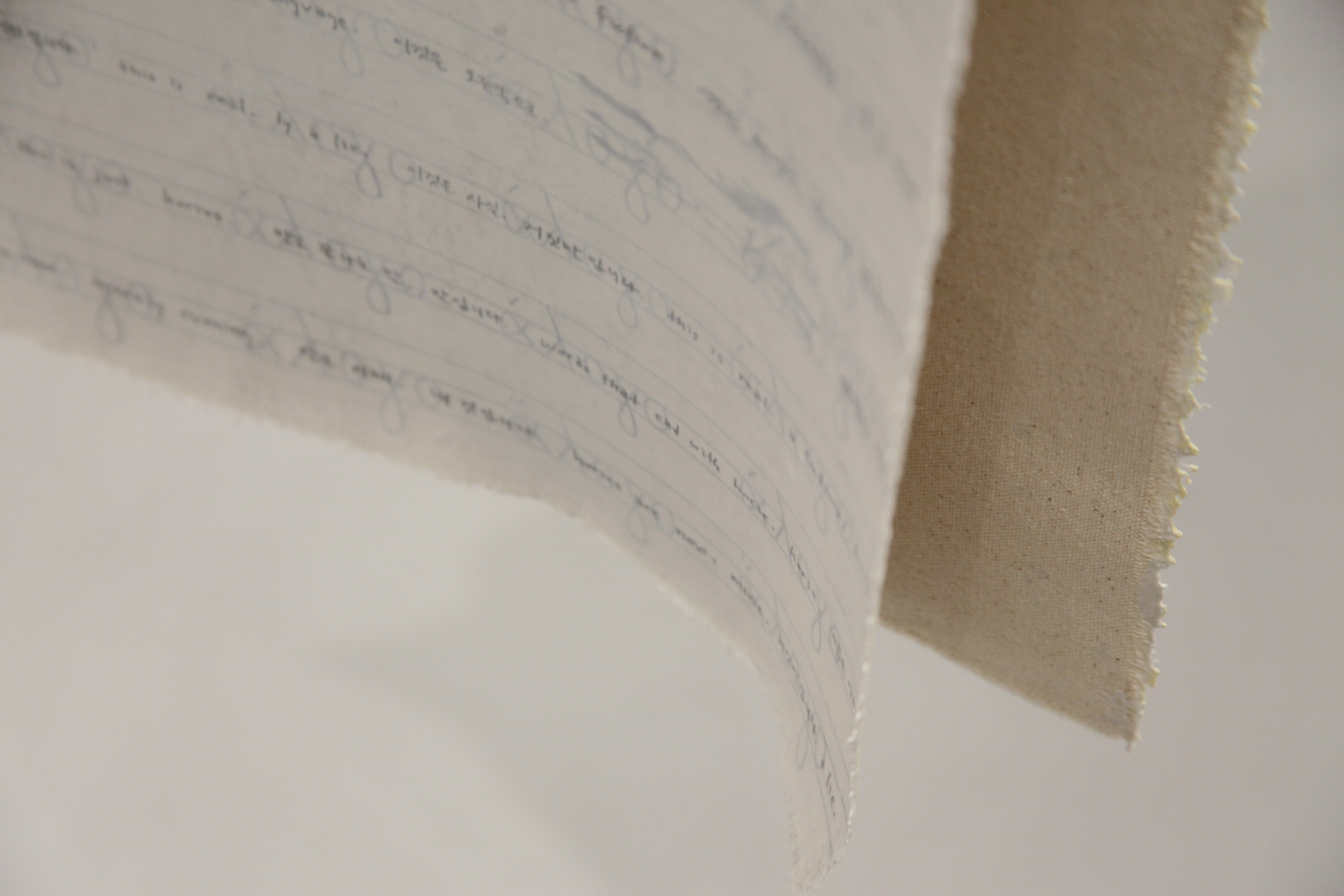

1. The Korean word 말 [mal] can encompass multiple meanings, including talk, word, speech, language, and story. At the same time, 말 [mal] also means horse.

2. I fidget with 말 [mal]. I obsessively retrieve 말 [mal] that might otherwise be forgotten, only to grapple with their lingering discomfort. When I find an interesting combination of 말 [mal], I keep rolling them around in my head. They remain in an unresolved, unsettled state. And they wander through the stream of the shower, above my pillow, in my dreams, and inside my sketchbook. Like a child endlessly fiddling with a stone in their pocket, I fidget with these words.

3. As much as I love 말 [mal] in the sense of talk, word, or language, I am obsessed with 말 [mal] as horse. Horse is, in a way, a mistranslation of the 말 [mal] I’m drawn to. In this shitty translation, I find freedom and joy.

4. Shitty translation has opened up new possibilities in translation. Every translation damages the original while simultaneously adding new meaning. For instance, when my Korean surname 이 [iː] is romanized as “Lee” instead of “Eee,” it loses its original pronunciation. However, my English name “Leo Lee” gains a playful rhythm. Similarly, a shitty translation damages the original, yet it generates new possibilities. 말 [mal] cannot simply be translated as talk or word. So I translate it as horse. This act of violation both exposes and embraces the limits of translation. It appears to stray further from the original, but perhaps, by doing so, it comes closer. By rendering 말 [mal] as horse, I have discovered an indefinite domain located between Korean and English, between word and horse, between text and image.

5. This indefinite domain is mine. I have found a place where I am most free between languages. It is somewhere between universally understood domains, and thus is personal. Yet it is still situated within the framework of language. Within this framework, I attempt violations. Here, I can be both universal and personal, both naked and safe.

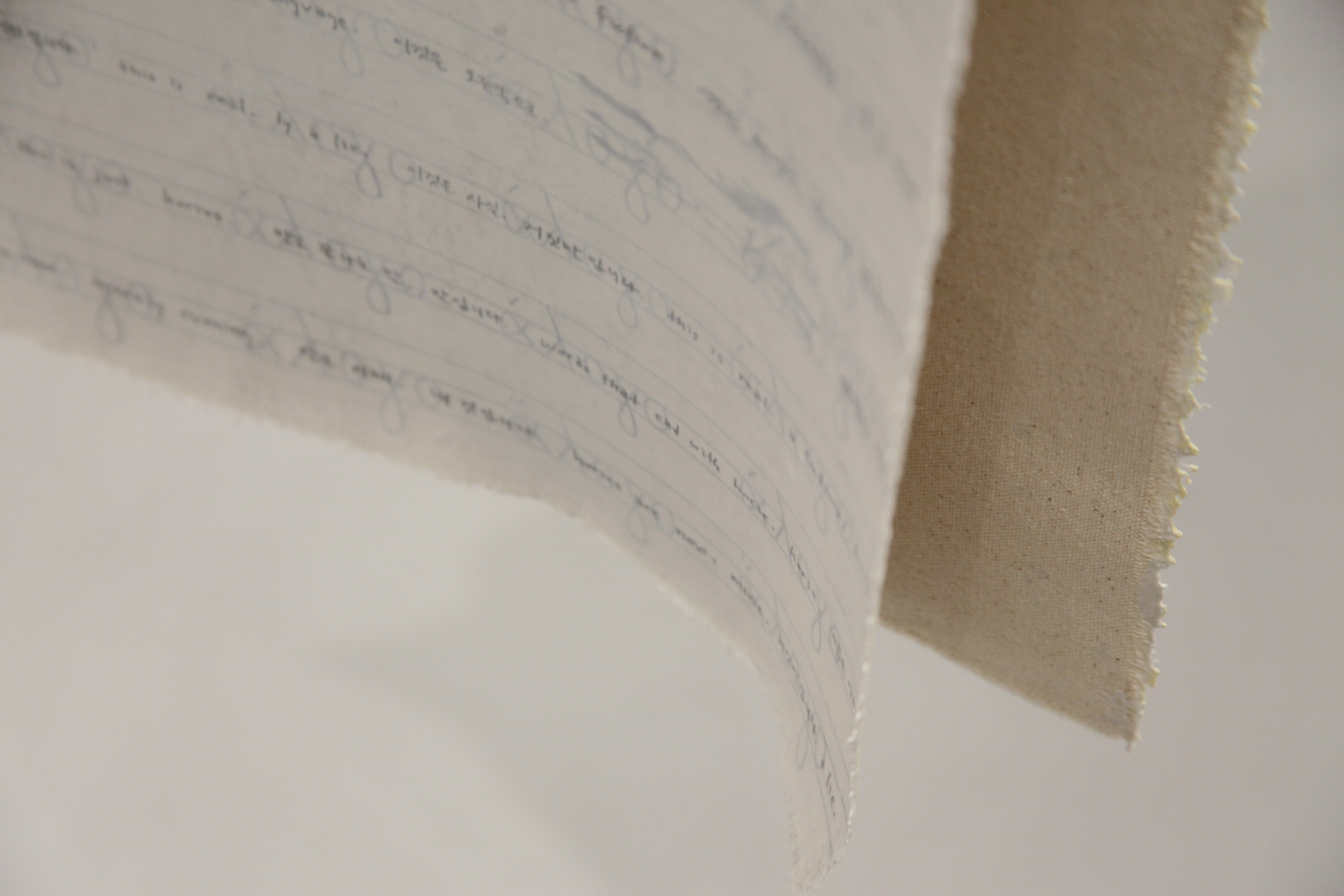

6. I play freely within language, a human-constructed system. Wordplay. I bring these words into the material world and touch them with my hands. I inscribe, bury, unearth, and play with them. I fumble with them through acts of cutting, pasting, and layering.

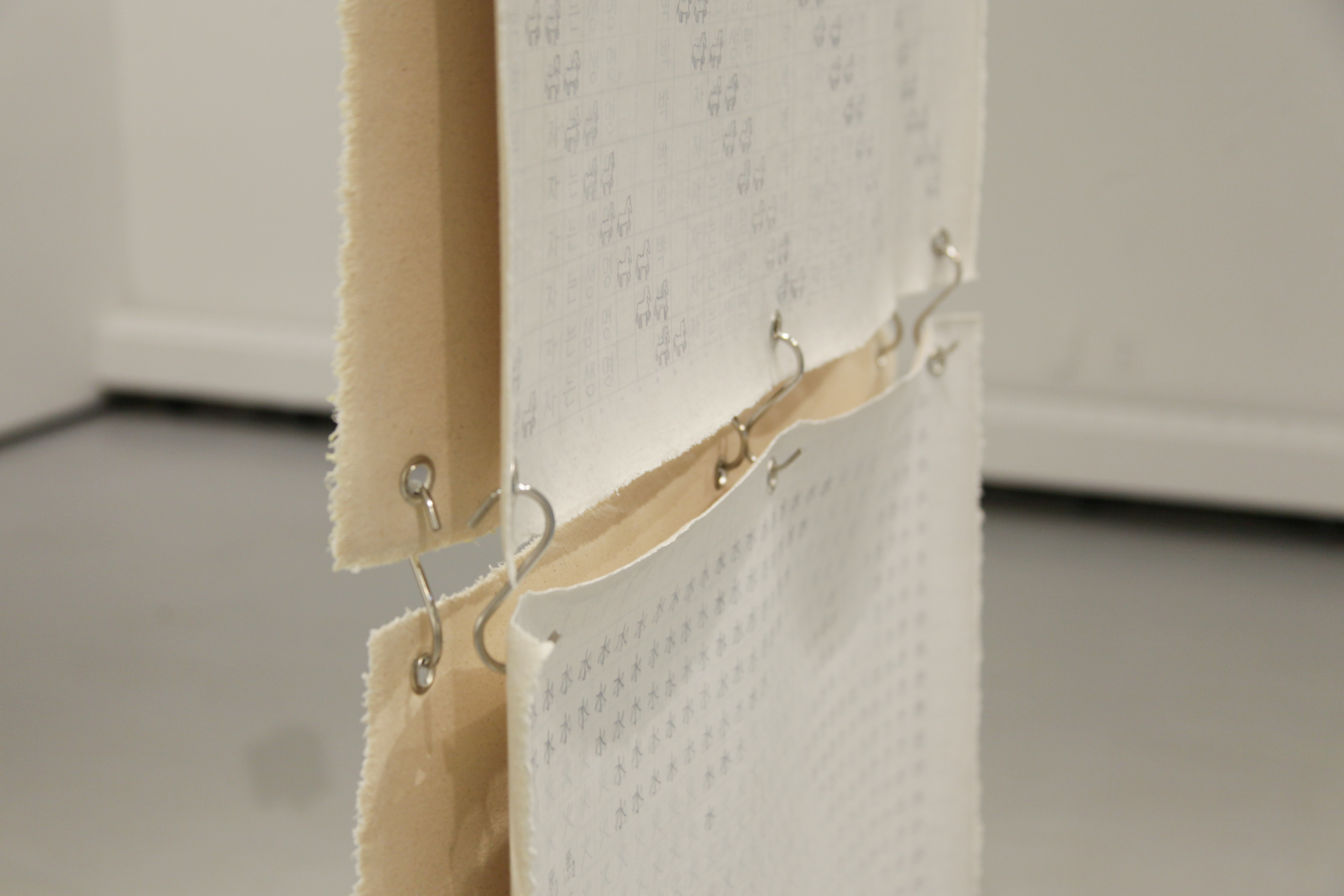

7. When people die, they leave their 말 [mal] behind. When 말 [mal] die, they leave their hide behind. This is a twist on a Korean saying, and my current body of work revolves around this concept. To inscribe and bury words by hand, I mixed a material that mimics skin. By mixing acrylic materials such as molding paste and gel, I formed a translucent substance and spread it thinly over the canvas. Each work contains at least 10, sometimes up to 60, layers, with words embedded between them. Words vanish into the skin, while others resurface.

8. I repeat 말 [mal] over and over. I keep writing the same words, stacking countless layers, reintroducing words, hand sewing numerous panels together, and drawing square after square. This repetitive, self-inflicted practice becomes the process of my work. Within cycles of repetition and the constraints of the grid, I feel safe.

-

2024 ~

-

2024

-

2023

-

2024

𓃗 materials↓

canvas, acrylic medium, graphite, acrylic paint, acrylic ink, waxed thread, oil paint, aluminum sheet metal, zinc screws, stainless steel grommets, stainless steel s-hooks

𓃗 dimensions↓

variable

𓃗 words↓

1. The Korean word 말 [mal] can encompass multiple meanings, including talk, word, speech, language, and story. At the same time, 말 [mal] also means horse.

2. I fidget with 말 [mal]. I obsessively retrieve 말 [mal] that might otherwise be forgotten, only to grapple with their lingering discomfort. When I find an interesting combination of 말 [mal], I keep rolling them around in my head. They remain in an unresolved, unsettled state. And they wander through the stream of the shower, above my pillow, in my dreams, and inside my sketchbook. Like a child endlessly fiddling with a stone in their pocket, I fidget with these words.

3. As much as I love 말 [mal] in the sense of talk, word, or language, I am obsessed with 말 [mal] as horse. Horse is, in a way, a mistranslation of the 말 [mal] I’m drawn to. In this shitty translation, I find freedom and joy.

4. Shitty translation has opened up new possibilities in translation. Every translation damages the original while simultaneously adding new meaning. For instance, when my Korean surname 이 [iː] is romanized as “Lee” instead of “Eee,” it loses its original pronunciation. However, my English name “Leo Lee” gains a playful rhythm. Similarly, a shitty translation damages the original, yet it generates new possibilities. 말 [mal] cannot simply be translated as talk or word. So I translate it as horse. This act of violation both exposes and embraces the limits of translation. It appears to stray further from the original, but perhaps, by doing so, it comes closer. By rendering 말 [mal] as horse, I have discovered an indefinite domain located between Korean and English, between word and horse, between text and image.

5. This indefinite domain is mine. I have found a place where I am most free between languages. It is somewhere between universally understood domains, and thus is personal. Yet it is still situated within the framework of language. Within this framework, I attempt violations. Here, I can be both universal and personal, both naked and safe.

6. I play freely within language, a human-constructed system. Wordplay. I bring these words into the material world and touch them with my hands. I inscribe, bury, unearth, and play with them. I fumble with them through acts of cutting, pasting, and layering.

7. When people die, they leave their 말 [mal] behind. When 말 [mal] die, they leave their hide behind. This is a twist on a Korean saying, and my current body of work revolves around this concept. To inscribe and bury words by hand, I mixed a material that mimics skin. By mixing acrylic materials such as molding paste and gel, I formed a translucent substance and spread it thinly over the canvas. Each work contains at least 10, sometimes up to 60, layers, with words embedded between them. Words vanish into the skin, while others resurface.

8. I repeat 말 [mal] over and over. I keep writing the same words, stacking countless layers, reintroducing words, hand sewing numerous panels together, and drawing square after square. This repetitive, self-inflicted practice becomes the process of my work. Within cycles of repetition and the constraints of the grid, I feel safe.

-

2025

𓃗 materials↓

canvas, acrylic medium, graphite, acrylic paint, acrylic ink, waxed thread, oil paint, aluminum sheet metal, zinc screws, stainless steel grommets, stainless steel s-hooks

𓃗 dimensions↓

variable

𓃗 words↓

1. The Korean word 말 [mal] can encompass multiple meanings, including talk, word, speech, language, and story. At the same time, 말 [mal] also means horse.

2. I fidget with 말 [mal]. I obsessively retrieve 말 [mal] that might otherwise be forgotten, only to grapple with their lingering discomfort. When I find an interesting combination of 말 [mal], I keep rolling them around in my head. They remain in an unresolved, unsettled state. And they wander through the stream of the shower, above my pillow, in my dreams, and inside my sketchbook. Like a child endlessly fiddling with a stone in their pocket, I fidget with these words.

3. As much as I love 말 [mal] in the sense of talk, word, or language, I am obsessed with 말 [mal] as horse. Horse is, in a way, a mistranslation of the 말 [mal] I’m drawn to. In this shitty translation, I find freedom and joy.

4. Shitty translation has opened up new possibilities in translation. Every translation damages the original while simultaneously adding new meaning. For instance, when my Korean surname 이 [iː] is romanized as “Lee” instead of “Eee,” it loses its original pronunciation. However, my English name “Leo Lee” gains a playful rhythm. Similarly, a shitty translation damages the original, yet it generates new possibilities. 말 [mal] cannot simply be translated as talk or word. So I translate it as horse. This act of violation both exposes and embraces the limits of translation. It appears to stray further from the original, but perhaps, by doing so, it comes closer. By rendering 말 [mal] as horse, I have discovered an indefinite domain located between Korean and English, between word and horse, between text and image.

5. This indefinite domain is mine. I have found a place where I am most free between languages. It is somewhere between universally understood domains, and thus is personal. Yet it is still situated within the framework of language. Within this framework, I attempt violations. Here, I can be both universal and personal, both naked and safe.

6. I play freely within language, a human-constructed system. Wordplay. I bring these words into the material world and touch them with my hands. I inscribe, bury, unearth, and play with them. I fumble with them through acts of cutting, pasting, and layering.

7. When people die, they leave their 말 [mal] behind. When 말 [mal] die, they leave their hide behind. This is a twist on a Korean saying, and my current body of work revolves around this concept. To inscribe and bury words by hand, I mixed a material that mimics skin. By mixing acrylic materials such as molding paste and gel, I formed a translucent substance and spread it thinly over the canvas. Each work contains at least 10, sometimes up to 60, layers, with words embedded between them. Words vanish into the skin, while others resurface.

8. I repeat 말 [mal] over and over. I keep writing the same words, stacking countless layers, reintroducing words, hand sewing numerous panels together, and drawing square after square. This repetitive, self-inflicted practice becomes the process of my work. Within cycles of repetition and the constraints of the grid, I feel safe.

-

2024

-

2024

-

2023

-

2024